Weight: 2

Candidates should be able to determine and configure fundamental system hardware.

Objectives

- Enable and disable integrated peripherals

- Differentiate between the various types of mass storage devices

- Determine hardware resources for devices

- Tools and utilities to list various hardware information (e.g. lsusb, lspci, etc.)

- Tools and utilities to manipulate USB devices

- Conceptual understanding of sysfs, udev, dbus

/sys/proc/dev- modprobe

- lsmod

- lspci

- lsusb

Find out about the hardware

An operating system (OS) is system software that manages computer hardware, and software resources, and provides common services for computer programs. It sits on top of the hardware and manages the resources when other software (Sometimes called an userspace program) asks for it.

Firmware is the software on your hardware that runs it; Think of it as a built-in OS or driver for your hardware. Motherboards need some firmware to be able to work too.

Firmware is a type of software that lives in hardware. Software is any program or group of programs run by a computer.

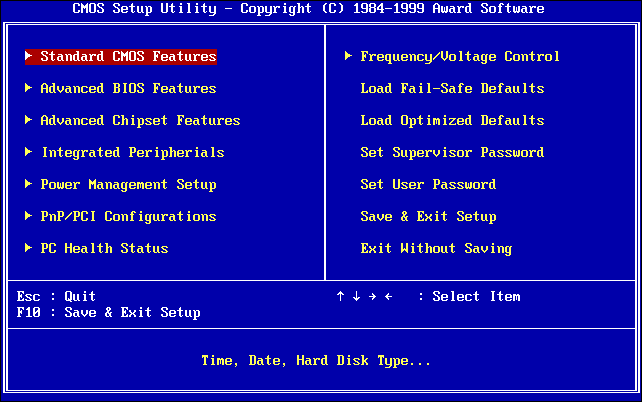

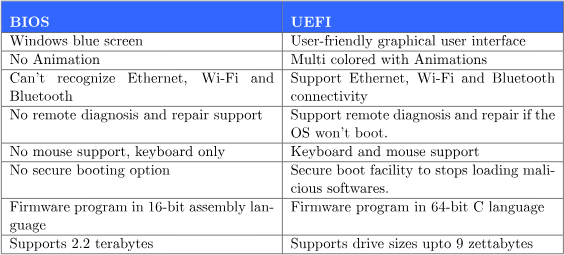

1. BIOS (Basic Input/Output System). Old and redundant. It is intractable through a text menu-based system and it boots the computer by accessing the first sector of the first partition of your hard disk (MBR). This is not enough for modern systems and most systems use a two-step boot procedure.

1. BIOS (Basic Input/Output System). Old and redundant. It is intractable through a text menu-based system and it boots the computer by accessing the first sector of the first partition of your hard disk (MBR). This is not enough for modern systems and most systems use a two-step boot procedure.

2. UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface). Started as EFI in 1998 in Intel. Now the standard. Uses a specific disk partition for boot (EFI System Partition (ESP)) and uses FAT. On Linux it's located on

2. UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface). Started as EFI in 1998 in Intel. Now the standard. Uses a specific disk partition for boot (EFI System Partition (ESP)) and uses FAT. On Linux it's located on /boot/efi and the files use the .efi extension. You need to register each bootloader.

Peripheral Devices

These are device interfaces.

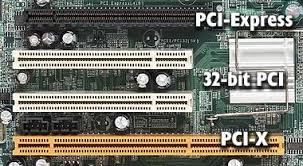

PCI

Peripheral Component Interconnect. Enables the user to add extra components to the Motherboard. Now most servers use PCI Express (PCIe)

- Internal HDD.

- PATA (old)

- SATA (serial & up to 4 devices) (II-III)

- SCSI (parallel & up to 8 devices) (Small Computer System Interface)

- External HDD. Fiber (Providing a high-speed data connection). SSD over USB

- Network cards. RJ 45 (Registered Jack 45)

- Wireless cards. IEEE 802.11

- Bluetooth. IEEE 802.15 (Short-range (up to 10m) wireless technology standard)

- Video accelerators. Hardware circuits on a graphics card that speed up full-motion video.

- Audio cards

SSD vs HDD

- SSDs are faster (reads up to 10 times and writes up to 20 times faster), quieter, smaller, more durable, and consume less energy, while HDDs are cheaper and offer more storage capacity and easier data recovery if damaged.

- SSDs don't have moving parts such as actuator arms and spinning platters like hard drives (an SSD uses flash memory without any moving parts). That's one reason why SSDs can withstand accidental drops and other shocks, vibration, extreme temperatures, and magnetic fields better than HDDs.

- HDDs tend to last around 3-5 years, SSDs can last up to 10 years or more. (Current SSDs have reserve capacities. These storage spaces aren't available to the user, but are used to repair damaged cells, so to speak. The defect cells are replaced with brand-new reserve cells; this procedure is called “Bad-Block-Management”. Thus, SSD storage cells in normal operation last a lifetime.)

Network cards vs Wireless cards

- NIC (Network Interface Card) provides computing network connectivity on a computing device to Ethernet network in Home or Office through RJ45 port. Wireless Adapter Card provides wireless connectivity to computing network enabled by Access Points on premises (in home or office) on a Computing Device.

- Wireless cards are installed on an industrial computer is used to enable wireless connectivity to the internet.

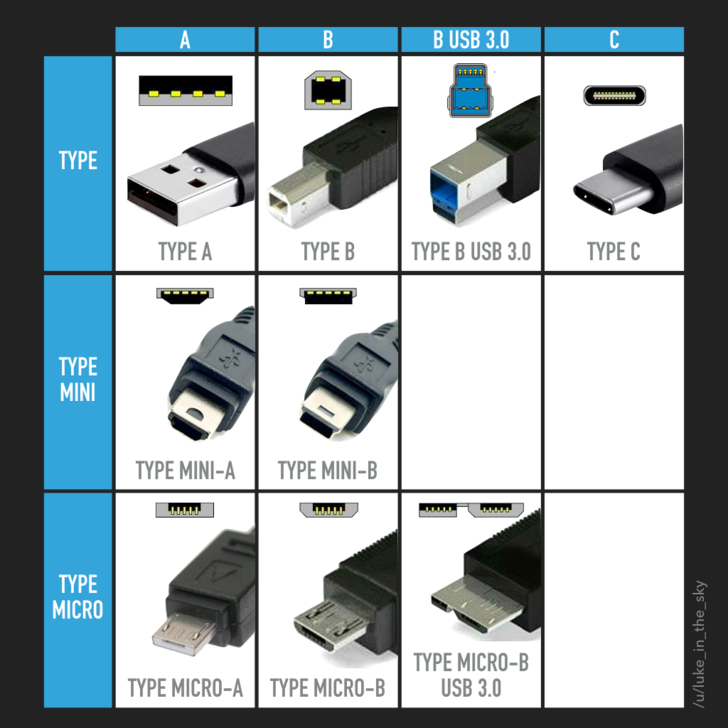

USB

Universal Serial Bus. Serial and need fewer connections.

- 1 (12Mbps), 2 (480Mbps), 3 (PCI.e 2.0 Bus:5Gbps, PCI.e 3.0 Bus:10Gbps, PCI.e 3.2 Bus:20Gbps, PCI.e 4.0 Bus:40Gbps)

- A, B, C

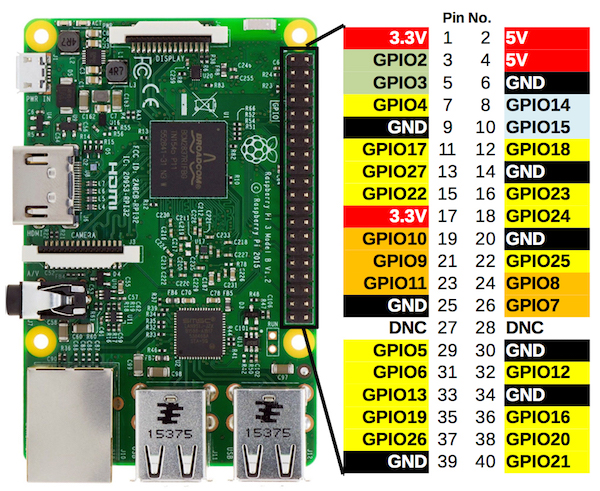

GPIO

General Purpose Input Output.

- To control other devices

- Examples include Arduino, raspberrypi, etc.

Sysfs

Sysfs is a pseudo file system provided by the Linux kernel that exports information about various kernel subsystems, hardware devices, and associated device drivers from the kernel's device model to user space through virtual files.[1] In addition to providing information about various devices and kernel subsystems, exported virtual files are also used for their configuration.

Sysfs is mounted under the /sys mount point.

jadi@funlife:~$ ls /sys

block bus class dev devices firmware fs hypervisor kernel module power

All block devices are at the block and bus directory has all the connected PCI, USB, serial, ... devices. Note that here in sys we have the devices based on their technology but /dev/ is abstracted.

udev

udev (userspace /dev) is a device manager for the Linux kernel. As the successor of devfsd and hotplug, udev primarily manages device nodes in the /dev directory. At the same time, udev also handles all user space events raised when hardware devices are added into the system or removed from it, including firmware loading as required by certain devices.

There are a lot of devices in /dev/ and if you plug in any device, it will be assigned a file in /dev (say /dev/sdb2). udev lets you control what will be what in /dev. For example, you can use a rule to force your 128GB flash drive with one specific vendor to be /dev/mybackup every single time you connect it and you can even start a backprocess as soon as it connects.

In essence, udev serves as the custodian of the /dev/ directory. It abstracts the representation of devices, such as a hard disk, which is identified as /dev/sda or /dev/hd0, irrespective of its manufacturer, model, or underlying technology.

root@funlife:/dev# ls /dev/sda*

/dev/sda /dev/sda1 /dev/sda2 /dev/sda3 /dev/sda5 /dev/sda6

If a program wants to read/write from/to a device, it will use the corresponding file in /dev to do so. This can be done on character devices or block devices. When listing, a b or c will indicate this:

root@ocean:~# ls -ltrh /dev/ # Partial output is shown

crw-rw---- 1 root tty 4, 1 Dec 15 2019 tty1

crw-rw-rw- 1 root root 1, 5 Dec 15 2019 zero

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 1, 0 Dec 15 2019 ram0

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 253, 0 Dec 15 2019 /dev/vda

dbus

D-Bus is a message bus system, a simple way for applications to talk to one another. In addition to inter-process communication, D-Bus helps coordinate process lifecycle; It makes it simple and reliable to code a "single instance" application or daemon and to launch applications and daemons on demand when their services are needed.

proc directory

This is where the Kernel keeps its settings and properties. This directory is created on ram and files might have write access (say for some hardware configurations). You can find things like:

- IRQs (interrupt requests)

- I/O ports (locations in memory where CPU can talk with devices)

- DMA (direct memory access, faster than I/O ports)

- Processes

- Network Settings

- ...

$ ls /proc/

1 1249 1451 1565 18069 20346 2426 2765 2926 3175 3317 3537 39 468 4921 53 689 969 filesystems misc sysvipc

10 13 146 157 18093 20681 2452 2766 2929 3183 3318 354 397 4694 4934 538 7 97 fs modules timer_list

1039 1321 147 1572 18243 21 2456 28 2934 3187 34 3541 404 4695 4955 54 737 acpi interrupts mounts timer_stats

10899 13346 148 1576 18274 21021 2462 2841 2936 3191 3450 3550 41 47 4970 546 74 asound iomem mtrr tty

10960 13438 14817 158 1859 21139 25 2851 2945 32 3459 357 42 4720 4982 55 742 buddyinfo ioports net uptime

11 13619 149 16 18617 2129 2592 2852 2947 3202 3466 36 43 4731 4995 551 75 bus irq pagetypeinfo version

11120 13661 15 1613 18781 214 26 2862 2948 3206 3467 3683 44 4756 5 56 77 cgroups kallsyms partitions version_signature

11145 13671 150 1630 1880 215 27 2865 2952 3208 3469 3699 4484 4774 50 577 8 cmdline kcore sched_debug vmallocinfo

1159 13927 151 1633 1882 2199 2707 2866 2955 3212 3470 37 4495 4795 5008 5806 892 consoles keys schedstat vmstat

1163 14 1512 1634 19 22 2708 2884 2957 3225 3474 3710 45 48 5013 60 9 cpuinfo key-users scsi zoneinfo

1164 14045 1515 1693 19061 2219 2709 2887 2961 3236 3475 3752 4506 4811 5077 61 904 crypto kmsg self

1170 14047 152 17 19068 23 2710 2891 3 324 3477 3761 4529 4821 5082 62 9061 devices kpagecount slabinfo

1174 14052 153 17173 19069 23055 2711 2895 3047 3261 3517 3778 4558 484 5091 677 915 diskstats kpageflags softirqs

12 1409 154 1732 19075 2354 2718 29 3093 3284 3522 38 4562 4861 51 678 923 dma loadavg stat

1231 1444 155 17413 2 2390 2719 2904 31 3287 3525 3803 46 4891 52 679 939 driver locks swaps

1234 1446 156 17751 20 24 2723 2908 3132 3298 3528 3823 4622 49 5202 680 940 execdomains mdstat sys

1236 145 1563 18 2028 2418 2763 2911 3171 33 3533 3845 4661 4907 525 687 96 fb meminfo sysrq-trigger

The numbers are the process IDs! There are also other files like cpuinfo, mounts, meminfo, ...

$ cat /proc/cpuinfo

processor : 0

vendor_id : GenuineIntel

cpu family : 6

model : 42

model name : Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-2520M CPU @ 2.50GHz

stepping : 7

microcode : 0x15

cpu MHz : 3195.312

cache size : 3072 KB

physical id : 0

siblings : 4

core id : 0

cpu cores : 2

apicid : 0

initial apicid : 0

fpu : yes

fpu_exception : yes

cpuid level : 13

wp : yes

flags : fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush dts acpi mmx fxsr sse sse2 ss ht tm pbe syscall nx rdtscp lm constant_tsc arch_perfmon pebs bts nopl xtopology nonstop_tsc aperfmperf eagerfpu pni pclmulqdq dtes64 monitor ds_cpl vmx smx est tm2 ssse3 cx16 xtpr pdcm pcid sse4_1 sse4_2 x2apic popcnt tsc_deadline_timer aes xsave avx lahf_lm ida arat epb xsaveopt pln pts dtherm tpr_shadow vnmi flexpriority ept vpid

bogomips : 4983.79

clflush size : 64

cache_alignment : 64

address sizes : 36 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

power management:

processor : 1

vendor_id : GenuineIntel

cpu family : 6

model : 42

model name : Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-2520M CPU @ 2.50GHz

stepping : 7

microcode : 0x15

cpu MHz : 3010.839

cache size : 3072 KB

physical id : 0

siblings : 4

core id : 0

cpu cores : 2

apicid : 1

initial apicid : 1

fpu : yes

fpu_exception : yes

cpuid level : 13

wp : yes

flags : fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush dts acpi mmx fxsr sse sse2 ss ht tm pbe syscall nx rdtscp lm constant_tsc arch_perfmon pebs bts nopl xtopology nonstop_tsc aperfmperf eagerfpu pni pclmulqdq dtes64 monitor ds_cpl vmx smx est tm2 ssse3 cx16 xtpr pdcm pcid sse4_1 sse4_2 x2apic popcnt tsc_deadline_timer aes xsave avx lahf_lm ida arat epb xsaveopt pln pts dtherm tpr_shadow vnmi flexpriority ept vpid

bogomips : 4983.79

clflush size : 64

cache_alignment : 64

address sizes : 36 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

power management:

We can also write here. Since I'm on an IBM Lenovo laptop I can turn my LED on and off by writing here:

root@funlife:/proc/acpi/ibm# echo on > light

root@funlife:/proc/acpi/ibm# echo off > light

One more traditional example is changing the max number of open files per user:

root@funlife:/proc/sys/fs# cat file-max

797946

root@funlife:/proc/sys/fs# echo 1000000 > file-max

root@funlife:/proc/sys/fs# cat file-max

1000000

Another very useful directory here, is /proc/sys/net/ipv4 which controls real-time networking configurations.

All these changes will be reverted after a boot. You have to write into config files in

/etc/to make these changes permanent

Try yourself! Check the /proc/ioports or /proc/dma or /proc/iomem.

lsusb, lspci, lsblk, lshw

Just like ls but for pci, usb, ...

lspci

Shows PCI devices that are connected to the computer.

# lspci

00:00.0 Host bridge: Intel Corporation 2nd Generation Core Processor Family DRAM Controller (rev 09)

00:02.0 VGA compatible controller: Intel Corporation 2nd Generation Core Processor Family Integrated Graphics Controller (rev 09)

00:16.0 Communication controller: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family MEI Controller #1 (rev 04)

00:19.0 Ethernet controller: Intel Corporation 82579LM Gigabit Network Connection (rev 04)

00:1a.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family USB Enhanced Host Controller #2 (rev 04)

00:1b.0 Audio device: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family High Definition Audio Controller (rev 04)

00:1c.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port 1 (rev b4)

00:1c.1 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port 2 (rev b4)

00:1c.4 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port 5 (rev b4)

00:1d.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family USB Enhanced Host Controller #1 (rev 04)

00:1f.0 ISA bridge: Intel Corporation QM67 Express Chipset Family LPC Controller (rev 04)

00:1f.2 SATA controller: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family 6 port SATA AHCI Controller (rev 04)

00:1f.3 SMBus: Intel Corporation 6 Series/C200 Series Chipset Family SMBus Controller (rev 04)

03:00.0 Network controller: Intel Corporation Centrino Wireless-N 1000 [Condor Peak]

0d:00.0 System peripheral: Ricoh Co Ltd MMC/SD Host Controller (rev 07)

lsusb

Shows all the USB devices connected to the system.

# lsusb

Bus 002 Device 003: ID 1c4f:0026 SiGma Micro Keyboard

Bus 002 Device 002: ID 8087:0024 Intel Corp. Integrated Rate Matching Hub

Bus 002 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 001 Device 005: ID 04f2:b217 Chicony Electronics Co., Ltd Lenovo Integrated Camera (0.3MP)

Bus 001 Device 004: ID 0a5c:217f Broadcom Corp. BCM2045B (BDC-2.1)

Bus 001 Device 003: ID 192f:0916 Avago Technologies, Pte.

Bus 001 Device 002: ID 8087:0024 Intel Corp. Integrated Rate Matching Hub

Bus 001 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

lshw

Shows hardware. Might need root status to get the full list. Test it!

lsblk

Used for list devices that can read from or write to by blocks of data.

Loadable Kernel Modules

Linux like any other OS needs drivers to work with hardware. In Microsoft Windows, you need to install the drivers separately but in Linux, the system has most of the drivers built-in. But to prevent the kernel from loading all of them at the same time and to decrease the Kernel size, Linux uses Kernel Modules. Loadable kernel modules (.ko files) are object files that are used to extend the kernel of the Linux Distribution. They are used to provide drivers for new hardware like IoT expansion cards that have not been included in the Linux Distribution.

You can inspect the modules using the lsmod or manage them via modprobe commands.

lsmod

Shows kernel modules. They are located at /lib/modules.

root@funlife:/dev# lsmod

Module Size Used by

pci_stub 12622 1

vboxpci 23256 0

vboxnetadp 25670 0

vboxnetflt 27605 0

vboxdrv 418013 3 vboxnetadp,vboxnetflt,vboxpci

ctr 13049 3

ccm 17731 3

dm_crypt 23172 1

bnep 19543 2

rfcomm 69509 8

uvcvideo 81065 0

arc4 12608 2

videobuf2_vmalloc 13216 1 uvcvideo

intel_rapl 18783 0

iwldvm 236430 0

x86_pkg_temp_thermal 14205 0

intel_powerclamp 18786 0

btusb 32448 0

videobuf2_memops 13362 1 videobuf2_vmalloc

videobuf2_core 59104 1 uvcvideo

v4l2_common 15682 1 videobuf2_core

mac80211 660592 1 iwldvm

coretemp 13441 0

videodev 149725 3 uvcvideo,v4l2_common,videobuf2_core

media 21963 2 uvcvideo,videodev

bluetooth 446190 22 bnep,btusb,rfcomm

kvm_intel 143592 0

kvm 459835 1 kvm_intel

snd_hda_codec_hdmi 47547 1

crct10dif_pclmul 14307 0

6lowpan_iphc 18702 1 bluetooth

crc32_pclmul 13133 0

snd_hda_codec_conexant 23064 1

ghash_clmulni_intel 13230 0

snd_hda_codec_generic 68914 1 snd_hda_codec_conexant

aesni_intel 152552 10

snd_seq_midi 13564 0

snd_seq_midi_event 14899 1 snd_seq_midi

aes_x86_64 17131 1 aesni_intel

mei_me 19742 0

lrw 13287 1 aesni_intel

iwlwifi 183038 1 iwldvm

These are the kernel modules that are loaded. Use modinfo to get more info about a module; If you want.

If you need to add a module to your kernel (say a new driver for hardware) or remove it (uninstall a driver) you can use rmmod and modprobe.

# rmmod iwlwifi

And this is for installing the modules:

# insmod kernel/drivers/net/wireless/iwlwifi.ko

But nobody uses insmod because it does not understand dependencies and you need to give it the whole path to the module file. Instead, use the modprobe command:

# modprobe iwlwifi

you can use

-fswitch to FORCErmmodto remove the module even if it is in use

If you need to load some modules every time your system boots do one of the following:

- Add their name to this file

/etc/modules - Add their config files to the

/etc/modprobe.d/

| ← Prepare your Lab | 101.2 Boot the System → |